- Home

- Sarah McCraw Crow

The Wrong Kind of Woman Page 2

The Wrong Kind of Woman Read online

Page 2

Sam kept playing. There was something wrong with all these people, the other Clarendon guys, the crowd of faculty in the big front parlor, the buzz of voices rising and falling as the faculty talked about whatever they usually talked about, campus gossip, probably. To the faculty, this was just another reception at President Weissman’s house.

Sam let himself remember jazz band rehearsals, sharing sheet music with Oliver whenever Sam played clarinet rather than guitar. He’d made Oliver laugh about Schuyler DePeyster’s trumpet playing. Oliver had thought Sam was funny, even talented. Oliver had been a friend. The weirdness of being here now was too much. He had to get out of here, he needed a joint, a drink, something.

“Some gig, huh,” Stephen said. They were in between songs, and nobody was paying any attention. The other Clarendon guys had left, back to their frats and Friday afternoon beers.

“Let’s take a break,” Sam said. “Maybe pack it in.” They could help Larry take down his drum kit and slip out through the porch door. No one would notice, or care.

* * *

Virginia woke in the dark to a sour, fuzzy mouth. She reached across the bed, but the sheets were blank and cool: no Rebecca. This day hadn’t ended yet. After Virginia’s family and friends had come to the house for ham sandwiches and bourbon, her mother had put her to bed, a cool hand to her forehead as if she were a feverish child, and she’d slept.

As ripples of talk drifted upstairs, Virginia lay there listening. June’s voice rose above the others, strident and bossy, and the house smelled like Norfolk, salty, fatty ham and tomatoey Brunswick stew. She made herself get up. Oliver’s soft windbreaker lay draped over the armchair, where he’d thrown it a few days ago, and she slipped it on.

Downstairs, she heard the TV—in the den, Rebecca sat with Molly from next door watching The Courtship of Eddie’s Father. The show’s cheerful background music soothed her, and she sank down next to Rebecca, willing her brain to say the things a mother said to her child on a night like tonight, but nothing came. She took in that Rebecca’s and Molly’s eyes were full, tearing up at Bill Bixby and his darling little boy. Rebecca rested her head on Virginia’s shoulder and Virginia put an arm around her. But after only a few minutes Rebecca scooted away. “Can you go brush your teeth, Mom? Your breath is really bad.”

“Okay.” Virginia pushed up to standing and headed to the kitchen. At the kitchen table, her mother and sisters turned to look at her, all of them smiling too much, and June stood to pull her into a hug. Momma was still in her funeral suit, an ancient black thing with a peplum, a party apron protecting it, and she leaned over a memo pad, pen in hand: when in doubt, make a list.

“Ah, my little baby Ginny,” Momma said.

June and Marnie bustled around Virginia’s small kitchen, pulling things out of the fridge and the oven. June was small and nimble, and an early white streak ran through her dark hair. Like June, Virginia had Daddy’s dark eyes, but her own hair was mousy, not black-Irish dark like June’s.

Marnie, bigger and blonder than June, set a plate in front of Virginia—ham, broccoli casserole, rolls, butter—and a cup of coffee. Virginia took a bite of the casserole, pushed the plate away.

“You’ve got tons of food here,” June said. “I’ve got some Brunswick stew going for the freezer. Between that and the ham and all these casseroles, you’ll have dinners for weeks.”

Virginia nodded.

June and Marnie started in on Norfolk gossip, filling her in while entertaining themselves. Oh, and had she heard about Jimmy Burwell? “You know he’s a lawyer, UVA law, that’s right. Well, get this, he left his wife for another lawyer, yes, a woman lawyer! Doesn’t that beat all!”

Her sisters’ gossip washed over her and made her feel sick to her stomach.

“We’ll go to the store in the morning and pick up some more supplies, whatever you need,” June said. “But why don’t you come on home for a while?”

“Jesus, June,” Marnie said. “Give her a minute, would you?”

“It just seems like you don’t fit in here, Ginny,” June said. “Your friends seem—” She paused. “I mean, who are your friends?”

“Oh, she fits in fine,” Marnie said. “You’re afraid of the North, June, that’s what.”

“I am not,” June said. “It’s just too cold here. And now it’s snowing. There are camellias blooming along the side of my house. Camellias! Blooming. No snow.”

“I like the snow.” Virginia’s voice came out thin and squeaky. She wanted to say something about the snow softening up winter, which made her think of the hard ground, which made her think of Oliver, who’d loved the New Hampshire cold and the snow far more than she did. Tears gathered and stung.

“I will say that it’s kind of hard to get here,” Marnie said. “That tiny airplane, my God.”

“You used to love to watch the cardinals and the orioles,” June said. “Remember how we watched them together in the backyard when we were little?”

She nodded. They had birds in New Hampshire too, maybe even better birds. Purple finches, bluebirds, yellow-black-and-white bobolinks swooping over the hayfields north of town.

But she was too tired to say anything. Maybe her mother and sisters could carry her home to Norfolk, and she’d stay wrapped up in gossip and mild weather. Rebecca could go to the academy, where her sisters’ kids went; the academy had started admitting girls ten years ago, and her sisters said it was a wonderful school, rigorous and traditional. And Rebecca could go to the beach in the summer and dance to swing-band music at night, as Virginia used to do. Lose a husband, change a life, was that it? Oliver had been fascinated, in a kind of anthropological way, by Virginia’s family, and how they did things down there, and how Norfolk couldn’t decide if it was a small town or a city. She tried for a second to imagine finding someone down there, maybe one of those lawyers that her sisters had just gossiped about, although Jimmy Burwell—there was nothing to recommend him. One of her brother Rolly’s old friends? God, no. She started to cry again; she was thinking about the wrong things.

“Oh, honey.” Marnie scooted her chair close, pulling Virginia’s head onto her lap.

Virginia let her head rest on Marnie’s wide leg, trying to sort her jumble of thoughts into some kind of order. Oliver. Rebecca. Her mother. Her sisters. Her brother. Oliver. Where did she belong? She swallowed a sob, took a breath, wiped her eyes with the handkerchief that President Weissman had handed to her. Weeks ago, it seemed, but the reception had only been this afternoon.

“I—” She was about to say yes, all right, maybe she and Rebecca would come home to Norfolk—but something stopped her.

“It’s okay,” Marnie said. “It’ll be okay.”

Virginia heard the plaintive strains of a Simon & Garfunkel song coming from the den; Rebecca and Molly were listening to music on Oliver’s hi-fi. Now Simon or maybe Garfunkel sang about how he was gone, how he didn’t know where. Virginia wanted to hear more of those shimmery harmonies, but the song had finished.

Chapter Two

Virginia found a parking spot across the street from the Clarendon library. She sat in the car, gathering herself, turning her mind to the upper-level class in Dutch and Flemish art she was due to teach next semester. The Northern Baroque. Rembrandt and Hals portraits, how they never flattered, but sympathized. Still lifes full of decay and death. Jan Steen’s jolly tavern scenes, talking back to Amsterdam’s dour church fathers. Vermeer’s utter silence.

She forced herself to get out of the car. Pushing through the library’s revolving side door, she trotted down the worn stairs to the basement. She cut through the study room, which ran the full width of the library, to get to the art history department on the far side.

Only a handful of boys were at the study tables this afternoon. To her right, the enormous panels of the González mural, whose monumental figures with burning eyes told the story of the Ameri

cas in a way no Clarendon boy would ever think to do. Such a foolish place to display the mural, a basement that smelled of damp and mold. The mural needed restoration; maybe the administration hoped the mural, with its Communist themes, all those skulls and burning eyes, would crumble from the plaster and disappear. For now, those eyes glared out at the scattering of boys who sprawled at the long tables.

A long time ago, Oliver had lured her here with the González mural. Think of it, he’d said. Clarendon can’t be all bad if they commissioned a González in the ’20s.

Oliver had gotten only a slim set of offers: Clarendon College, Lake Forest College and two even smaller schools in Wisconsin. Harvard had passed him over, a rejection that had thrown him so badly that she’d turned herself into his cheerleader. What a wonderful town for Rebecca to grow up in, she’d said about one of the spots in Wisconsin, but he must have picked up on her disappointment, judging by the manic way he’d shown her the Clarendon campus. That first visit, her own unfinished dissertation on John Singleton Copley’s surfaces never came up because she had Rebecca; Rebecca was her work now. Taking care of Rebecca and getting over the miscarriages.

Upstairs, Virginia leaned into Arthur Gage’s doorway, and he stood quickly, motioning her in. He wore a flannel shirt, no tie—exam-week wear. She began to thank him for taking on her class those last weeks, grading all her papers.

Arthur shook his head, waving off her thanks. “Not at all, it was the least I could—but not a problem. Would you like some tea?” He told her how glad he was to see her, and he hoped things were going well enough, all things considered. He didn’t leave room for her to get in a word, not that she wanted to tell him how things were going. Oliver was dead, that was how things were going.

“I’m afraid we need to cancel the spring Northern Baroque class.” He paused, raked the hair off his forehead. “Not enough students signing up. And perhaps it’s a bit too specialized for our men.”

She nodded, waiting.

“Though it was well attended last year.” He steepled his hands against his mouth, not saying the rest: not enough students had signed up because Virginia wasn’t Dan Mason, whom she’d been hired to fill in for while he was on sabbatical in Italy. The Clarendon boys wanted a man, a robust man with a doctorate that they could confidently call “Dr.” or “Professor.” Not an undereducated woman like her. Or maybe he was only being kind. Maybe word had gotten around that she wasn’t much of a teacher. A mere substitute, margarine instead of butter.

“Right.” Despite all she knew about Dutch and Flemish art, more than enough to teach a handful of boys and one girl on exchange from Mt. Holyoke, she hadn’t finished, never mind published, her dissertation. At home, on the floor next to her desk in the bedroom, the stack of books and monographs on John Singleton Copley bristled with the scraps of paper she’d marked them with years ago. Now and then she shuffled her index cards, typed a few more sentences. Sometimes she drove to Boston to look again at the Copleys, and Copley’s Paul Revere gazed back at her, chin in hand, daring her to write something when too much had already been written. She felt her fists balling in her lap. She unclenched them and smoothed her skirt; she hated this skirt, wool plaid, neither long nor short. It was the kind of thing June would wear, if June lived in New Hampshire.

“I heard the English department is desperate for help,” he said. “Administrative work, but it’s been a mess there since Chapman left and Mrs. Smith retired.”

She nodded, as if she’d want to take the place of jowly, ancient Mrs. Smith.

“At any rate, you’ll have more time to spend with your...daughter?”

How dare he bring Rebecca into this? Virginia pushed back, stood up and left his office without answering. You’ve forgotten your manners, dear, she could hear Momma saying, as she hurried back down the hall, down the stairs and back through the library’s study room. If only she had the glaring, magical power of those huge Aztec gods in the mural, she’d cast an angry spell on smug Arthur Gage, let him be tormented for a while.

* * *

At home, when Momma asked how the meeting had gone, Virginia answered that it had gone as expected, feeling a flush of rage and embarrassment at the way she’d run off in the middle of it.

Once again, Momma was in New Hampshire, and for a week now she’d bustled around Virginia’s kitchen, packing Rebecca’s lunches, rinsing out tinfoil and sandwich bags to reuse, and taking Rebecca to piano lessons. Momma pestered Virginia to reply to all those pale condolence notes and to get through the stack of Oliver-related paperwork, but also to rest as much as possible. Momma had insisted on taking Virginia to the doctor, to get you looked over, as if she were six years old. At the doctor’s office, Momma asked about a prescription for something just to tide my Ginny over. Tide her over till when? Until Oliver came back?

“I forgot to tie up the pot roast,” Momma said. “Who knows how it will turn out.”

Before Virginia could reassure her, the phone rang: Louise Walsh. “We’re trying to get Shirley Chisholm up here,” Louise Walsh said, with barely a hello. “The new congresswoman, from Brooklyn? She’s doing good work with Bella Abzug. There’s already been some talk about her running for president. Extreme long shot, but I’m sure you heard that speech she gave in Congress about the equal rights amendment a couple months ago? It was so electrifying that we thought we’d raise some money to help her come up here for the primary—”

“I’m sorry, but that’s not my thing,” Virginia said. No, she hadn’t heard Shirley Chisholm’s speech about equal rights. If politics had ever been her thing, it certainly wasn’t right now. “I’m a little out of—”

“Right, but I thought that since you’re—I thought you might—” Louise stumbled over her words.

You thought wrong, Virginia kept herself from saying. “Maybe some other time.” She hung up, fueled by irritation.

Louise Walsh. She strongly disliked Louise by the transitive property. Oliver used to get red in the forehead and temples when he’d talk about Louise, how Louise hijacked meetings with her crazy tangents, and how nobody ever stopped her, just let her go on and on. He was the only one who ever tried to keep meetings on track.

The faculty had almost gone to war with itself last year, when a handful of Clarendon boys, inspired momentarily by more activist schools, had taken over the administration building to protest ROTC recruiting, Virginia remembered. The national wave of sit-ins and takeovers had rolled onto the Clarendon campus, and some of the faculty had wanted to cancel classes in solidarity with the protesters. Louise was on the side of the protesters, Oliver on the side of practicality; cancel classes and too many boys would get drunk and start breaking things. Louise was always agitating about something, Oliver used to say.

“... But he’s a good man, honestly,” Momma was saying. “And from a good family.”

Virginia willed herself to listen to Momma’s chatter about Bryce Watson, Daddy’s banker. Momma still referred to Bryce Watson as Daddy’s banker, even though Daddy had been dead for fifteen years.

“I’m sure it will all turn out fine, I’ll just have to trim my sails a bit,” Momma said, about something to do with her investments and needing to budget better. The softness of faraway Norfolk hovered like a cloud around Momma. Those early-spring days, the redbuds and azaleas and dogwoods a haze of blooms.

Momma was still talking; now she’d moved on to her friend Liddy Reynolds. “Did I tell you that Liddy’s moving to the Outer Banks?” Liddy was the mother of one of Virginia’s childhood friends, Sandra. Sandra Reynolds had died in a car crash sophomore year, driving back from a frat party at Washington and Lee. Ah, Sandra.

Virginia’s girlhood friends had stayed close to home for college, while Virginia had headed north, to Smith. Long ago, home from college for the summer, Virginia could hear her old friends’ accents which until then she’d never noticed. “You wear too much black,” one of her

friends said. “She’s trying to be mysterious,” another said. They’d all laughed, Virginia too, but she felt this wall rising up between herself and her childhood friends.

Then there was Archer, who she’d gone on two dates with that summer. Arch Tazewell, with those dimples and long eyelashes and football shoulders—he played quarterback for Hampden-Sydney College. On their second date, he drove her to the crab place down at Lynnhaven Inlet, and they sat in the back room, a screened porch where they could look out at the Chesapeake Bay, flat-calm and silvery in the distance. She’d already asked him about football and lacrosse, about his summer ROTC duties. Now she pretended interest as he droned on about Hampden-Sydney’s traditions—was she aware of all the Virginia governors who’d gone there, back to the Revolutionary War? She wasn’t. She picked out the yellowish mustard from her third crab.

“It wouldn’t be natural to admit him, of course.” Arch was talking about a black man who’d applied to Hampden-Sydney last year; she snapped to.

“Who would he socialize with?” Arch said. “It’s like a bad joke.”

“A bad joke,” she repeated. “Why?”

“Don’t pretend you don’t know what I mean. You can’t have white and colored students together like that.” He chuckled, as if she’d said something stupid and now he’d have to correct her. “You know that we can’t be wrecking our traditions that way.”

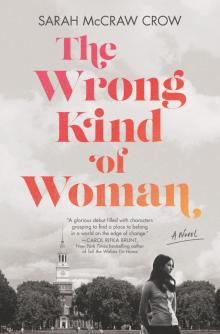

The Wrong Kind of Woman

The Wrong Kind of Woman